Reference: Visit website

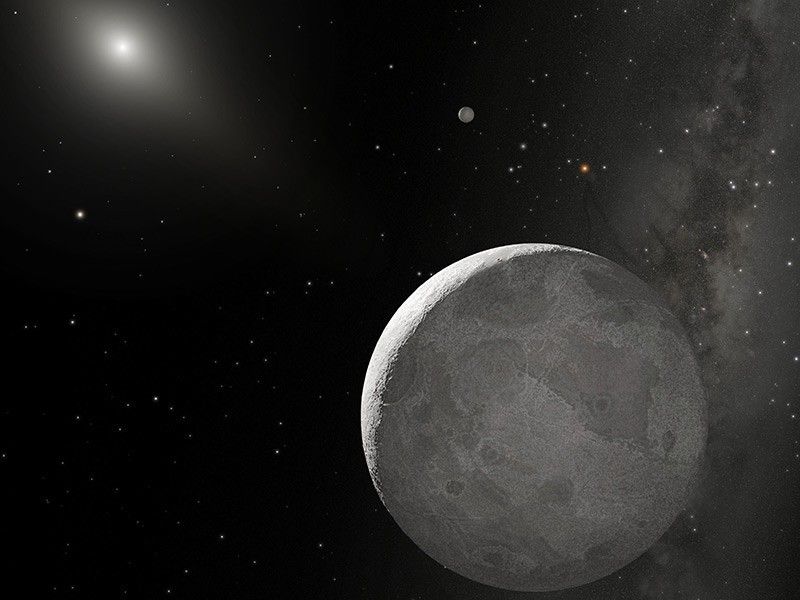

Reference: Visit websiteEight billion miles (14 billion kilometers) from Earth, at the solar system's ragged edge, lies Eris — a planet-sized oddball of a world that emerged unexpectedly from the darkness 20 years ago. Named for the capricious Greek goddess of discord, trouble-stirring Eris would doubtless be pleased that her celestial namesake caused even mild-mannered astronomers to quarrel, as its discovery caused the nature of what constitutes a "planet" to rear its controversial head.

With a magnitude of 18.7, Eris currently lies in the southern constellation Cetus the Whale, barely resolvable even by the world's largest telescopes. Due to its vast distance — some 95.6 astronomical units (AU; 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance) — its slow apparent progress across the sky makes it notoriously difficult to spot.

In 2001, astronomers at Palomar Observatory in California began systematically seeking planet-sized objects beyond Neptune. This time-consuming process targeted small pockets of the sky, utilizing powerful imaging software to identify anything that moved against the starry backdrop. To limit the number of false-positive data returns due to image resolution, the software excluded anything moving slower than 1.5 arcseconds per hour.

"Things like Eris were precisely what we were looking for when we started this survey in 2001," says Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology, who co-discovered Eris with Chad Trujillo, then of the Gemini Observatory, and David Rabinowitz of Yale University. "At that time, nothing had ever been found beyond about 60 AU, so we tuned the survey to concentrate on this area."

But an ironic consequence was that images of the slow-moving Eris, taken by Brown's team with the 48-inch (1.2 meters) Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar on Oct. 21, 2003, slipped entirely through the net, falling below their speed cutoff.

At the time of its discovery, Sedna lay at 90 AU — 8.3 billion miles (13.3 billion km) from the Sun, three times more distant than Neptune. And significantly, it moved at a paltry 1.75 arcseconds per hour. That prompted Brown's team to reanalyze their older data with lower limits on angular motion, then painstakingly sort through previously excluded images by eye.

No comments:

Post a Comment